FIFTY YEARS SINCE THE CLOSURE OF THE ROEBOURNE OLD RESERVE (GOODJARALLA)

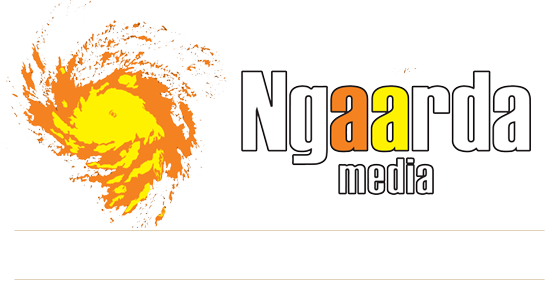

Late respected Yindjibarndi Elders, Yali and Wimiya King, outside their house in the Old Reserve, Roebourne.

ANALYSIS & OPINION

Sean-Paul Stephens with Ngarluma Elder Violet Samson

Today marks 50 years since the dismissal of the Whitlam Government — the first and only time in Australian history that a sitting prime minister was dismissed by the Governor-General. A defining event in Australia’s national story. But here in Ieramugadu (Roebourne), another anniversary has quietly passed; fifty years since the closure of the Roebourne Old Reserve — known as ‘Goodjaralla’ in language.

From the early 1900s, the government forcibly removed Ngarda-ngarli (Aboriginal people) from Ngurra (Country) and relocated the communities to designated “Native Reserves.” The Roebourne Old Reserve — Goodjaralla became one such place.

Yindjibarndi, Kuruma, Yaburrara, Marthudhunera, Banjima, Kariyarra peoples were forced onto Ngarluma Country, over the river from the colonial town of Roebourne. Not only was this a breach of human rights, but it was also a severe breach of cultural law.

The reserve remained open until 1975.

Under restrictive laws and protection policies, Aboriginal people were pushed off pastoral stations and denied freedom to live, travel or work without government permission. In Iermaugadu (Roebourne), Aboriginal people were banned from entering town limits after dark, and were not allowed to access local shops, schools, or public services.

Families who had lived on Country since time immemorial were gathered and confined to the Reserve — a flood-prone area two miles out of town — where the community were expected to live under supervision, away from the gaze of the non-Aboriginal population.

Throughout 1975 – the same year the Whitlam Government was famously dismissed –Ngarda-ngarli (Aboriginal) families were again forcibly removed. This time from the Old Reserve to a new settlement called The Village, built near the Roebourne cemetery. It marked the end of the Old Reserve – one of the most important places in Western Australian history.

For the older generation, some of whom are still alive today, this meant being dispossessed and moved three times: first, when taken from traditional Country; again, when the Old Reserve was closed in 1975; and once more, when The Village itself was condemned and demolished in 2012.

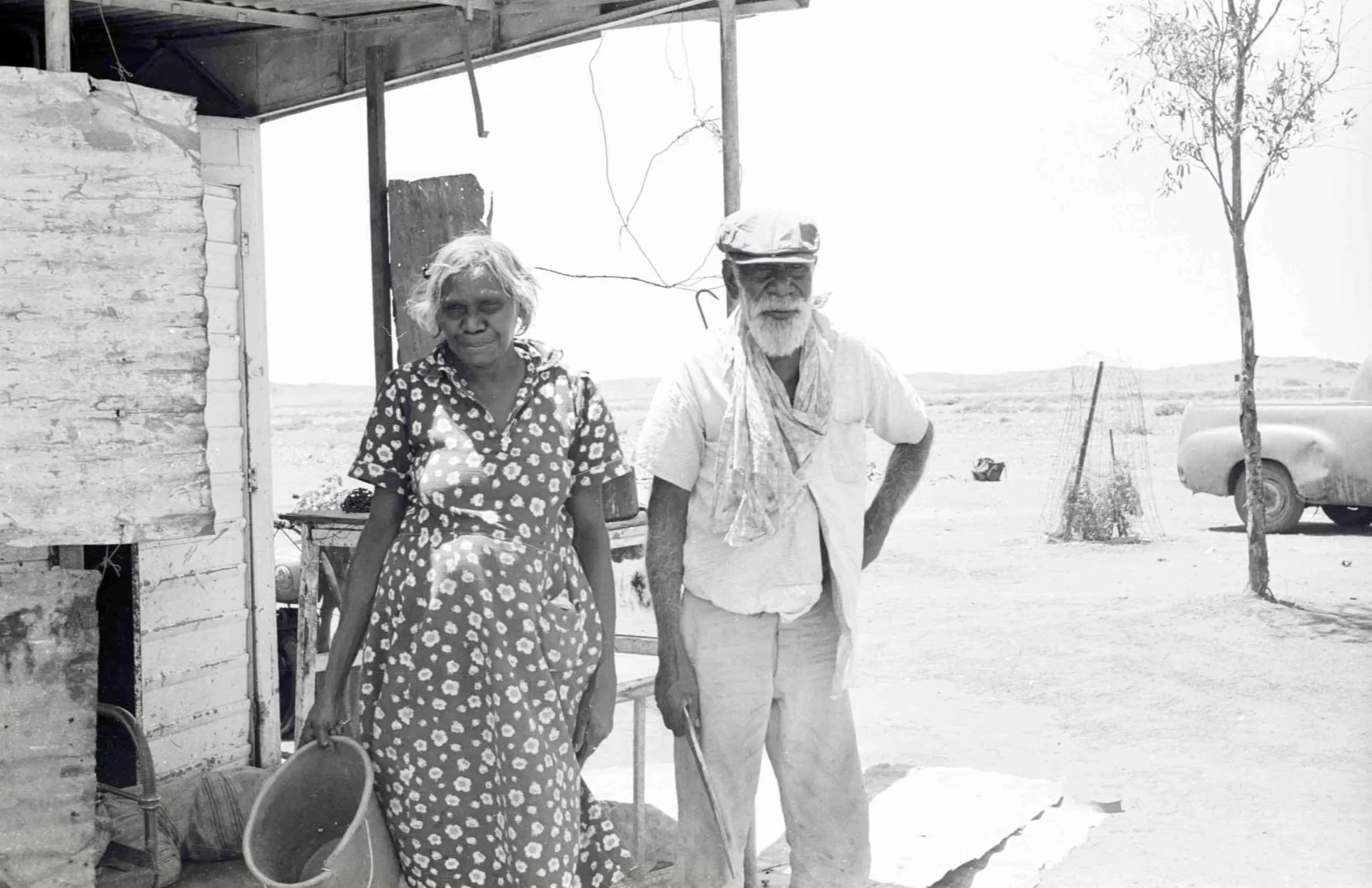

Figure 1 A family at the Reserve, living in a tent similar to the tent Violet Samson raised six children Source: State Library

Two Australias

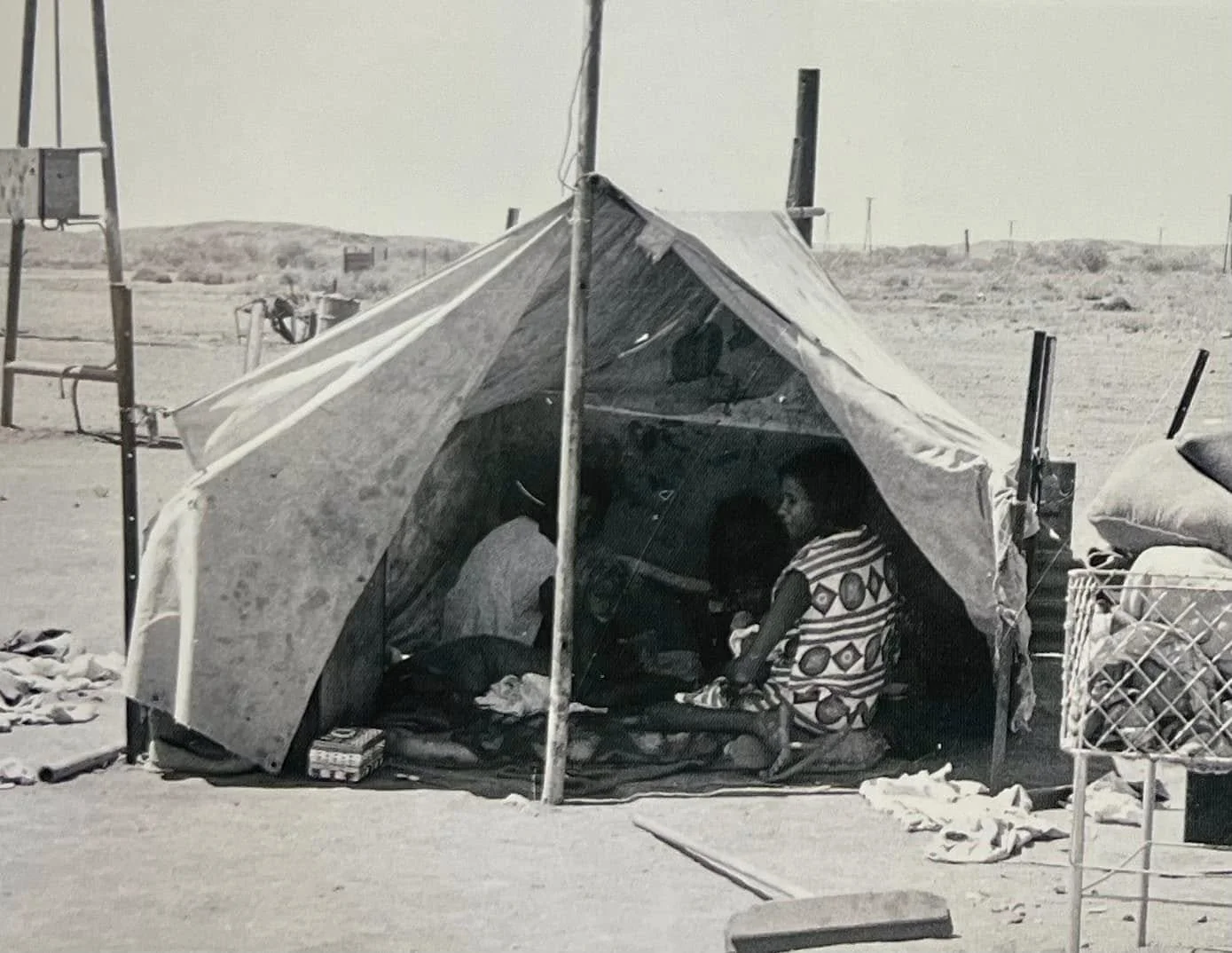

The 1970s were a time of transformation in Australia. The Sydney Opera House had just opened in 1973, symbolising a confident, modern nation. The Pilbara was booming with an expanding iron ore and petroleum industry, and new mining towns like Dampier, Wickham, and later Karratha, were being built. Wickham was built only eight kilometres away from the Old Reserve.

While towns grew with neat homes, green lawns and boats parked in driveways, Aboriginal families at the Reserve were still living in humpies and tents, drawing water from wells and washing clothes by hand in the Ngurin (Harding River).

Figure 2 Australia was celebrating the opening of the Sydney Opera House in 1973 while families were living in Reserves in places like Ieramugadu (Roebourne), Western Australia.

Senior Ngarluma Elder Violet Samson remembers the old reserve with both anguish and nostalgia.

“My house at the Old Reserve was a tent. Later, I moved into a humpy [shack]. The tent was made from canvas. I raised up six kids in that tent. We had to walk to a well to get water — send down a bucket, pull it up. There was a shower and gurna-maya [toilet] in the middle of the reserve that everyone had to share” Ms Samson said.

At its most populous, it is estimated that hundreds of Aboriginal people from across the Pilbara were forced to live at the Reserve. Ms Samson recalls it reached a point of overcrowding in the late 1960s. Speaking about Wickham’s construction eight kilometres away, she said it made Aboriginal people feel forgotten.

Figure 3 Senior Ngarluma Elder Violet Samson at her home in Ieramugadu (Roebourne).

“It made you feel no good. Government never really looked at us. It was very hard. Dampier [town] had been built, then Wickham — houses with green grass and people with boats — while we were still washing our clothes in the river nearby. But there were good times too at the Reserve… kids swimming in the river. Lots of laughing. But later on they built the Harding Dam and that blocked the river. No more swimming”Ms Samson said.

Figure 4 A family in front of their new house in Wickham in 1971, while Aboriginal people were still living in the Old Reserve only 8km away Source: State Library

Life at Goodjaralla

Elders recalls that while conditions were harsh, community life was rich. Families shared food, laughter, ceremony, and the care of children. Culture remained the foundation for survival. Lore was practiced at the Old Reserve.

Ceremony, which has remained strong since time immemorial – in western science,more than 65,000 years – continued to be practiced at the Reserve and later nearby Law Grounds.

In discussions with NYFL, Elders described the Old Reserve with nostalgia.

“Even though our Old People were forced to live in reserves like Goodjaralla, many had big smiles and laughed a lot. Our community grew strong. Our culture was our bedrock. We stayed connected to Ngurra (Country). Old people looked after the next generation,” one Elder told NYFL.

Figure 5 Lore ceremony continued to be practiced despite being forced to live at the Old Reserve

From Goodjaralla to The Village

When the Reserve was closed throughout 1975, families were again forced to move. This time into The Village — a cluster of State housing built behind the Roebourne cemetery, out of sight from the town. The move was presented as progress, but families were given no choice.

Yindjibarndi Elder Stanley Warrie, leader of the Cheeditha Aboriginal Community for decades. Cheeditha, also known as Old Woolshed, is a small community close to Ieramugadu.

According to Yindjibarndi Elder Stanley Warrie, the move opened up old wounds for the community.

“They pushed us out from Two Mile and said we had to move to The Village. It was hard — people didn’t want to go, that was our home. But we had no say,” Mr Warrie said.

Over time, The Village too became neglected and unsafe. By 2012, it was condemned and demolished — scattering families and erasing yet another part of the traumatic history of the north west.

The hardship of those early years at the Old Reserve and The Village left deep scars that still echo today — in health, housing, and social outcomes. Yet, the resilience and cultural strength have also been cemented. Today, Lore and ceremony remains strong – largely due to the strength and guidance of Elders who navigated the dispossession and anguish of the twentieth century.

Ms Samson reflects on the personal cost of living conditions at the Reserve.

“I only have two of my children left. Five of my children have passed away,” she said.

Her story represents the quiet strength of a generation that carried the weight of exclusion and dispossession with incredible dignity, humour, and love.

Today, the site of the Old Reserve is a vacant tract of land — no buildings, no signposts, no plaques to mark its story. Nothing stands there now except the collective memory of the Ieramugadu (Roebourne) community, which keeps its spirit alive through stories, songs, and shared remembrance. Each year, the community gathers at the Old Reserve to celebrate the Elders, known as the Old People’s birthday.

It is on the unmarked ground of the Old Reserve that generations of families laughed, sang, and raised their children.

From the people who endured those years grew the strength and leadership that define Ieramugadu (Roebourne) today. Many of those who were born and grew up I the Reserve and the Village are community leaders, sitting on the boards of organisations like the Ngarluma Yindjibarndi Foundation Ltd (NYFL) and Native Title organisations.

As the nation remembers the political upheaval of the Whitlam Dismissal, the Pilbara remembers a different kind of upheaval — one that speaks to survival, resilience and the enduring strength of community.

“Our old people went through hard times there, but they made it a place of culture, family and strength. We still carry that with us.” — Ngarluma Yindjibarndi Foundation Ltd