“RECONCILIATION IS BIGGER THAN THE REFERENDUM”: PATRICK DODSON’S ENDURING MESSAGE TO A NATION IN NEED OF TRUTH

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following program may contain images and voices of deceased persons.

BY ASAD KHAN

As Reconciliation Week unfolds across Australia, few voices carry the gravity and clarity of Patrick Dodson, Yawuru Elder, and often described as the “Father of Reconciliation”.

The former senator, who stepped down from federal parliament in 2023 to focus on his health, has been a leading force in the reconciliation movement since the 1990s, when he served as founding chair of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation—now Reconciliation Australia.

Dodson’s message is both direct and profound: reconciliation is not dead, despite the defeat of the Voice to Parliament referendum.

“The failure of the referendum is not the end of reconciliation,” Dodson said in a recent interview.

“Reconciliation is a far bigger project in this country. It’s about how we recognise the first people of this country and their rights.”

Nearly three decades after the council's formation, Dodson views this moment not as a closure, but as a continuation.

He credits the Uluru Statement from the Heart with charting a new course, one rooted in Voice, Treaty, and Truth. Each, he argues, remains vital.

“We’ve got a marvellous opportunity. We have governments at the state and national level that have generally supported Aboriginal people’s rights and interests,” he said.

“Now it’s time for them to be courageous.”

Dodson urged governments to act on the call from Uluru for a Makarrata Commission, a body to oversee treaty-making and truth-telling.

But reconciliation, he emphasised, cannot be left to politicians alone. He called on corporate leaders, community organisations, and everyday Australians to engage meaningfully, especially with principles like free, prior, and informed consent.

Dodson welcomed the Cook Government’s recent announcement of a redress scheme for Stolen Generations survivors in Western Australia. But he noted that many remain confused and anxious about how to access support.

“You can never compensate the hurt and pain and the abuse of people’s rights by putting a monetary sum on it,” he said.

“But at least there’s some contribution… and the recognition that this happened.”

He urged those affected to speak with local MPs, particularly Labor representatives for guidance. More importantly, he emphasised the role of community organisations in shaping and delivering the scheme so that it does not compound harm.

Reflecting on his own life, Dodson spoke about being forced to leave his homeland in Western Australia as a child to escape discriminatory laws. It was a painful experience that continues to inform his work.

“No one’s ever happy about doing that. And I certainly wasn’t,” he said.

“But I’ve had the privilege of coming back in adulthood and working with my people.”

He has never forgotten the injustices he witnessed, especially in his role as a commissioner in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

He recalled visiting Roebourne during the inquiry and the death of a young Aboriginal man there, as well as the tragic recent deaths in Alice Springs, including the recent death of a 24-year-old Aboriginal man, which have again shaken community.

“Those who have people in their care… they have a duty to look after people if they take them into custody. And if your rules are encouraging the opposite, they need to be revised,” he said.

Since 1991, the year the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) released its findings, there have been over 547 deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in custody.

Dodson called for the return of community-based accountability structures recommended by the Royal Commission committees that would work proactively with police and government agencies.

In the face of continuing systemic failure, Dodson’s belief in truth-telling remains strong. But it must be done properly, and respectfully.

“Truth-telling’s got to be a two-way street,” he said.

“Settler families and colonists have got to tell their stories, and they’ve got to accept responsibility for what their people did.”

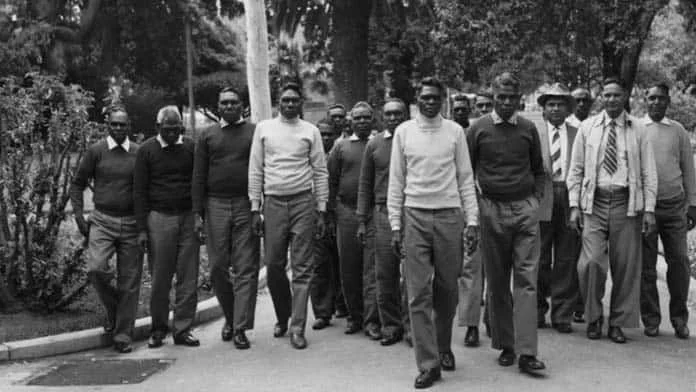

He pointed to the courageous Pilbara strike of the late 1940s, where Aboriginal workers walked off stations in protest of slavery-like conditions, and the establishment of the Yule River meetings that demanded government accountability long before it was fashionable to do so.

“There’s a lot of pride that people can take in that. Young people need to know that history in the Pilbara, the Kimberley, the Gascoyne—everywhere,”

For Dodson, reconciliation is as much about the future as the past. It is about crafting a shared national story—one that does not sanitise but includes and respects the truth.

“We need to bring all those threads together so we can have a common narrative,” he said.

“It’s not one that should be constantly driven just by the colonists’ version. We don’t live in a perfect world, but we need to build a better one—where First Peoples are recognised and respected as the First Peoples.”

As the country pauses to mark Reconciliation Week, Dodson’s voice is steady and unshaken. It is not optimism he offers, but resolve.

“We have to be hopeful. We have to be constructive. And we need to be committed,” he said.

For Patrick Dodson, reconciliation is not a moment; it’s a national obligation. And it’s not over.

Listen to Ngaarda Media’s Lead Journalist Asad Khan speak with Patrick Dodson: